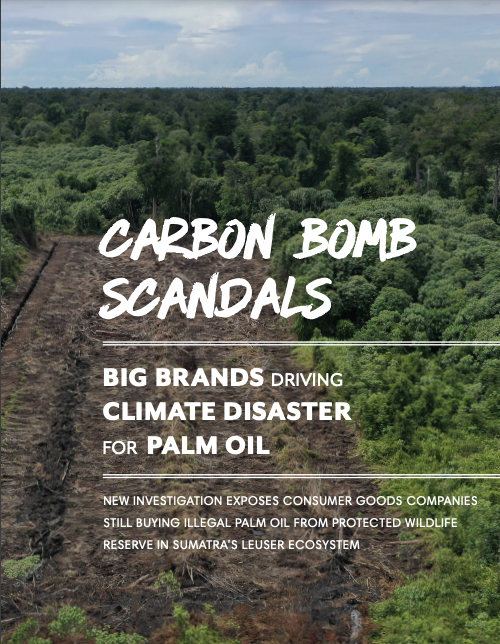

Latest scandal exposes how brands’ ‘No-deforestation’ systems are failing to stop sourcing of deforestation-linked illegal palm oil

In September 2022, RAN released the Carbon Bomb Scandals report proving that palm oil produced illegally in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve––a nationally protected nature reserve in the Leuser Ecosystem––continued to make its way into the products sold by Procter & Gamble, Mondelēz, Nestlé, Unilever, PepsiCo, Colgate-Palmolive, Ferrero, Nissin Foods and other Consumer Goods Forum members. The report named other brands, such as Mars and Kao, that were continuing to do business with the palm oil traders caught sourcing illegal palm oil from the reserve.

In recent weeks, three of the world’s biggest palm oil traders exposed in the scandal––Musim Mas, Wilmar, and Golden Agri Resources of the Sinar Mas Group––have issued reports confirming that their indirect suppliers had established illegal plantations within the protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. The reports also highlight an important precedent: agreements have been reached to return illegally established oil palm plantations to the authorities so they can be restored and managed as part of the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

Most major brands such as Mondelēz, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Colgate-Palmolive, Ferrero, and Nissin Foods have not responded to the Carbon Bomb Scandals report, despite the confirmation of their sourcing of palm oil from suppliers with illegal plantations in a nationally protected peatland and the Orangutan capital of the world.

RAN documented illegal palm oil plantations inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve that were operated by two suppliers––local elites called Mr. Mahmudin and Ibu Nasti. The sourcing of palm oil produced illegally, within protected areas, and on lands that were deforested or on carbon-rich peatlands, is a violation of each company’s “No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation” (NDPE) policy.

The report also sounded the alarm that deforestation is on the rise, not falling, in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve in Indonesia’s globally important Leuser Ecosystem. Despite this concerning trend––which is driven by the demand for palm oil–– the traders and brands named in the scandal have failed to announce an increase in investments and collective action to monitor and protect the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve from further destruction.

The Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve is located in the Singkil-Bengkung region which is one of the most critically important areas of the Leuser Ecosystem. Covering roughly 286,000 hectares (706,588 acres) in the southwest corner of the Leuser, Singkil-Bengkung is a worldwide hotspot for biological diversity and one of the highest-priority conservation landscapes on the planet. The region consists of the Singkil and Kluet peatlands––ancient, deep, and carbon-rich peatlands storing immense amounts of greenhouse gasses safely and naturally underground. Its peatlands and surrounding lowland rainforests also provide critical habitat for endangered Sumatran elephants, orangutans, and tigers. The area has been called the ‘orangutan capital of the world’ because it is home to the densest populations of orangutans to be found anywhere.

Palm Oil Traders Respond to the Carbon Bomb Scandals

Eight of the 15 traders named in the Carbon Bomb Scandals have issued public responses––including the publication of reports by three traders that undertook field verification exercises to investigate RAN’s allegations of illegal palm oil in their supply chains. Cargill, Bunge Loders Croklaan, Poliva, The Three, Ventura Foods, Allana, and Gemini edibles & fats have not yet issued a response.

Musim Mas issued updates detailing the results of its field verification of the findings in RAN’s initial report, and additional evidence published in response to Musim Mas and other traders initial denial of Mr. Mahmudin’s illegal plantation. Musim Mas confirmed during its field verification in November ‘that some part of Mr. Mahmudin’s farm extended inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.’ Musim Mas states that Mr. Mahmudin was not aware of this overlap and that part of its plantation was illegal as it had been established inside the boundaries of the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

In October 2020, one of Musim Mas’s supplying mills called PT. Bangun Sempurna Lestari (PT. BSL) decided to exclude supplies from Ibu Nasti and another mill PT. Global Sawit Semesta (PT. GSS) claims to have stopped sourcing from Mr. Mahmudin. The other supplier PT. Runding Putra Persada (PT. RPP) will continue to source from Mr. Mahmudin on the basis that he has agreed to an ‘action plan’ that will result in returning part of the farm located inside Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve to the government; declaring all oil palm farms that also belong to him; and creating and maintaining traceability records for all palm oil fresh fruit bunches (FFB) sources entering the collection points he controls that supply palm oil to nearby mills. This ‘action plan’ will be implemented in stages over 6 months from December 2022.

Musim Mas has accepted PT. RPP’s action plan and decided to continue to source from PT. RPP over the 6-month period despite the risks that doing so may result in ongoing sourcing of palm oil from illegal plantations within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

Wilmar and Golden Agri-Resources also issued responses which both linked to a joint report presenting the findings of a joint field verification exercise undertaken on 7-15th November 2022 to investigate RAN allegations against palm oil mill PT. Runding Putra Persada (PT. RPP), a palm oil broker called CV Buana Indah that was supplying the mill with palm oil FFB from Mr. Mahmudin.

Wilmar and GAR’s joint field verification also confirmed that Mr. Mahmudin had established illegal palm oil plantations over four-hectare areas of land located within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. Wilmar and GAR have also accepted PT. RPP’s action plan and will continue to source from the controversial mill despite the risks that doing so may result in ongoing sourcing from illegal plantations within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

The responses published by Musim Mas, Wilmar, and GAR all refer to ‘action plans’ agreed to with their suppliers, brokers selling palm oil FFBs to their supplying mills, and the non-compliant palm oil producers that they call smallholder farmers, despite both individuals being local elites with substantial land holdings––Mr. Mahmudin and Ibu Nasti. The agreement to ‘action plans’ was the same action that the traders took in response to RAN’s last scandal involving their sourcing of illegal palm oil from the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve in 2019. The approach of traders not suspending sourcing from all non-compliant suppliers is clearly ineffective given RAN has documented the same NDPE policy violations in the same protected area–– including by the same palm oil broker CV Buana Indah and mill PT. GSS-–– three years after the implementation of the 2019 ‘action plans.’ The action plans agreed upon this year include one important precedent: agreements have been reached to return illegally established oil palm plantations to the authorities so they can be restored and managed as part of the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. If this commitment is delivered through the restoration of the 4.5 hectares (approx. 11 acres) of illegal plantation, it will set an important precedent as over 300 hectares (approx. 740 acres) of illegal plantations have been established within the boundaries of the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

The Carbon Bomb Scandals show that major brands and the palm oil sector are still failing to enforce their ‘No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation’ policies. The weaknesses in the brands’ and traders’ approaches to monitoring, identifying, and addressing deforestation, new plantation development on peatlands, and non-compliant suppliers is a major contributor to their failure.

Unlike Musim Mas, Wilmar, and GAR, Apical of the Royal Golden Eagle did not undertake a field verification exercise of RAN’s findings, instead, it responded with a statement filled with inaccurate claims and denied that its supplier had illegal plantations and sourced from the collection point shown in RAN’s report. Apical did not respond to the additional evidence published by RAN in response to its denial of sourcing illegal palm oil or respond to the findings published by its peers that verified RAN’s evidence of Mr. Mahmudin’s illegal plantation.

Sime Darby––another palm oil producer and trader which has operations in Aceh––has issued a response that reiterates the false claims of its suppliers and did not disclose any requirements that it set for its suppliers to end their sourcing of illegal palm oil from the reserve.

A number of downstream palm oil processors that supply major brands with palm oil products have also issued responses.

AAK issued a response as its suppliers Apical, Musim Mas, and Golden Agri Resources were named in the scandal. AAK’s response refers to the actions taken by its suppliers, including the inaccurate claims made by Apical. AAK did not disclose any requirements that it set for its suppliers to end their sourcing of illegal palm oil from the reserve. AAK is working with Earthqualizer to monitor deforestation in its supply base and has mapped non-compliant land development within the wildlife reserve since the NDPE cut-off date of 31 December 2015. The results of this monitoring and mapping work have not yet been published.

Olam issued a response that claimed that “In relation to plantations owned by Mr. Mahmudin and Ibu Nasti – and those named in your report, PT Runding Putra Persada, PT Global Sawit Semesta and PT Bangun Sempurna Lestari – we can confirm that we do not source directly or indirectly from these suppliers and that they are not in our supply chains.” Olam has not responded to the additional evidence published by RAN which showed that its supplier Apical’s response––which is cited in Olam’s grievance list as a basis for its claim––is inaccurate and misleading. Given the lack of adequate traceability systems that have been confirmed by other traders’ field verification exercises, Olam and the mills and traders in its supply chain can not make any claims regarding the elimination of sourcing from non-compliant producers in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

Fuji Oil Group has responded but has not disclosed any requirements set for its suppliers to end their sourcing of illegal palm oil from the reserve. Its response refers to the claims made by its indirect supplying mill called PT. RPP that it had achieved 100% traceability. These claims have been shown to be false by Fuji Oil’s peers due to the mill not implementing its traceability system properly. Wilmar and GAR state in their verification report that “PT RPP mill obtains FFB supplies from its own plantations and dealers/agents. According to the 2021 TTP declaration report, PT RPP has achieved 100% FFB traceability. However, upon checking the FFB supplier list the team found that PT RPP has not been implementing the FFB traceability system properly.”

Fuji Oil claims that PT. RPP was not sourcing from the broker CV Buana Indah. This claim was also refuted by Wilmar and GAR’s investigation report which states “According to its (PT. RPP’s) FFB supplier list, CV BI is a new supplier registered in April 2022.” Fuji Oil has marked the complaint against PT. RPP ‘closed’ despite the clear evidence that it has been sourcing from a supplier with illegal plantations within the reserve. Fuji Oil cites inaccurate claims regarding PT. Global Sawit Semesta and Mr. Mahmudin that have been made by another supplier, Apical of the Royal Golden Eagle group. Fuji Oils claims to have stopped sourcing from Ibu Nasti via its supplying mill PT. Bangun Sempurna Lestari based on the findings that part of Ibu Nasti’s farm was also located within the protected area.

Major Brands and Consumer Goods Forum Fail to Respond Adequately to Illegal Palm Oil Scandal

In the Carbon Bombs Scandal report, RAN called on the brands exposed for sourcing illegal palm oil––and a collective of 400 consumer goods manufacturing companies in the Consumer Goods Forum––to stop the carbon bombs in their palm oil supply chains and scale up investments to protect the Leuser Ecosystem. Most major brands such as Mondelēz, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Colgate-Palmolive, Ferrero, and Nissin Foods have not responded to the scandal, despite the confirmation of their sourcing of palm oil from suppliers with illegal plantations in a nationally protected peatland and the ‘orangutan capital of the world.’ The Consumer Goods Forum, and its Forest Positive Initiative, have not issued a collective response despite the reports being hand delivered by activists to the CEOs of the biggest corporations committed to “Forest Positive” actions during the CGF’s events at last year’s Climate Week in New York City.

To date, only Procter & Gamble and Unilever have issued public responses to the Carbon Bomb Scandals. Procter & Gamble states that it has required “Tier 1 supplier to exclude Ibu Nasti from P&G’s supply chain” which is an action aligned with the recommendations made by RAN in our report. Instead of excluding both non-compliant suppliers from its supply chain, P&G states it ‘has aligned with Tier 1 supplier, Musim Mas, to collaborate with Mr. Mahmudin to return the 4.5 ha (approx. 11 acres) of encroached lands back to the authorities, and to work with Mr. Mahmudin to remediate the impacted lands.’ It is unclear the role P&G will play in the return of illegally planted areas to the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. The decision to continue sourcing from Mr. Mahmudin also shows that P&G is not adhering to its own “suspend and engage’ approach defined in its palm oil sourcing policy, which states ‘If our supplier does not acknowledge and take action to remediate the incident, we will suspend or eliminate palm purchases from that supplier. A supplier would need to have a documented action plan and demonstrate meaningful progress to be considered for reinstating supply agreements ‘If the land in question is already producing Fresh Fruit Bunches (“FFB”), supplier will ensure no FFB or palm from the area is supplied to P&G.’ In its December 2022 update to is grievance list, P&G once again failed to announce a suspension of sourcing from its supplier Royal Golden Eagle–– a controversial supplier that is driving deforestation in the Leuser Ecosystem via its palm oil arm Apical and is violating the rights of Indigenous communities across its timber operations in nearby concessions in North Sumatra.

Unilever’s response to the scandal is also inadequate as it did not disclose any requirements that it set for its suppliers to end their sourcing of illegal palm oil from Mr. Mahmudin & Ibu Nasti’s illegal plantations in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve and the mills and refineries shown in our investigation to be sourcing illegal palm oil. Unilever’s suspended supplier list fails to name Mr. Mahmudin, Ibu Nasti, PT. Runding Putra Persada, PT. Global Sawit Semesta, PT. Bangun Sempurna Lestari and the traders that persist in supplying it with palm oil grown at the expense of the Leuser Ecosystem.

The lack of adequate response from brands shows the systems the brands have in place to implement their NDPE policies and respond to non-compliance are failing after a decade of making commitments to end the sourcing of deforestation-fuelled and illegally produced palm oil. This is clearly shown in RAN’s Keep Forest Standing Scorecard which ranks the ten biggest brands’ performance in addressing deforestation and human rights violations in their forest-risk commodity supply chains.

Landscape-level action is needed to save the Singkil-Bengkung Region from palm oil driven destruction

Despite the growing threats to the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve, there have been no announcements of individual or collective investments in landscape-level actions to halt deforestation for palm oil across the three districts in the Singkil-Bengkung region, including in the response issued by Procter & Gamble, Wilmar, Golden Agri Resource, Apical, and other traders. A collaborative forest and monitoring initiative has yet not been established in the Singkil-Bengkung region and remains a priority for collaborative action in 2023.

Only Unilever refers to its commitment to “supporting a landscape program in the Leuser Ecosystem in Aceh with IDH Sustainable Trade Initiative, and other partners, suppliers, and stakeholders.” Unilever also reported on its landscape programs in northeast Aceh in late 2022. The emergence of landscape and jurisdictional programs is seen as a positive opportunity for collective action as these programs focus on protection and restoration, improving monitoring, and supporting livelihoods. To date, IDH’s programs are not being implemented in the two districts in the Singkil-Bengkung region where the illegal plantations exposed in the Carbon Bomb Report are located––Aceh Selatan and Subulussalam. However, a new program is being established by IDH, Apical and local organizations in the neighboring district of Aceh Singkil.

Musim Mas has taken some landscape-level actions through the establishment of a smallholder hub in the Singkil-Bengkung region––with support from AAK and Nestlé. This hub was established in 2020, after RAN’s last illegal palm oil scandal. The hub aims to build the capacity of government agricultural offices and smallholder farmers with knowledge of best practices for palm oil production, including NDPE requirements. As of December 2022, they have trained 892 Smallholders in Aceh Singkil and 476 Smallholders in Aceh Subulussalam––two of the three districts where the Singkil-Bengung region is located. They have not yet established a program in Aceh Selatan––the district where Mr. Mahmudin’s illegal plantation is located and where deforestation outside concessions by local elites is on the rise at an alarming scale. Musim Mas is working with Earthqualizer to monitor deforestation in its supply base, and on smallholder and social forestry programs in Aceh Singkil, and has communicated a willingness to support the establishment of a collaborative monitoring and response system for the region.

Traceability systems are failing to stop brands’ sourcing of deforestation-linked illegal palm oil

A major barrier to the effective implementation of NDPE policies is the failure of the brands to achieve traceability in their palm oil supply chains. Traceability means knowing the location where all palm oil they source was produced. The lack of adequate traceability systems means these corporations can’t monitor their supply chains adequately or monitor and identify all of their suppliers that are engaging in deforestation or expanding into peatlands. If the brands don’t know the plantations and farms that their suppliers––the traders––are sourcing from there is no way they can claim to be sourcing legally produced palm oil that is ‘deforestation-free’ and not grown at the expense of the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve or the threatened forests in the Leuser Ecosystem.

During the field verification exercises, the traders confirmed, once again, that the mills and brokers they were sourcing from had completely inadequate traceability systems––even in cases where mills had been claiming through self-reported data to have achieved 100% traceability. Suppliers caught sourcing illegal palm oil from the wildlife reserve are not recording and tracing all the palm oil FFBs suppliers, or data collection is patchy and inconsistent due to the brokers they are sourcing from not knowing or disclosing their sources. One supplier (PT. RPP) that was claiming 100% traceability was found to not be implementing the FFB traceability system properly. Another mill (PT. GSS) that had traceability procedures after RAN’s 2019 scandal were not implementing their procedures, especially for their new suppliers. Another mill claims to have a “first mile’ traceability mechanism that collects data related to legality and farm locations––but it was unaware that its supplier had both legal and illegal plantations. None of the mills had dedicated teams running and monitoring the traceability process.

The underlying reason why “first mile” traceability systems––systems that track to the farm or plantation level– have not been established by this network of suppliers around the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve is the lack of investment by brands and traders to ensure all current and potential suppliers are supported to comply with their NDPE policies and commitments to not source from suppliers destroying the Leuser Ecosystem. This urgently needs to change. The future of the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve and its surrounding lowland rainforests in the Singkil-Bengkung region which provide critical habitat for endangered Sumatran elephants, orangutans, and tigers depend on it.

2023 Must Be A Game Changing Year for the Implementation of No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation policies in the Leuser Ecosystem

RAN is a small nonprofit organization with very limited resources and only a small investigation team conducting the sorts of investigations that lead to the Carbon Bomb Scandals report and our other Leuser Watch investigations. The fact that we are able to find cases of ongoing sourcing from suppliers with illegal palm oil plantations and other violations of brands’ No Deforestation pledges every time we look for them is clear evidence that the serious issues we are raising are in fact just the tip of the iceberg of an ongoing, systemic failure in the efforts of global consumer goods companies to truly cut conflict palm oil from their supply chains.

With the last viable habitat of species like the Sumatran orangutan, elephant, rhino, and tiger––all critically endangered and at imminent risk of extinction in the wild––continuing to be destroyed by relentless palm oil plantation development, the situation is urgent and the stakes are high. The overall trend of an increase in deforestation in the Singkil-Bengkung region in 2022 and 2023 is extremely worrying. However, it is not all bad news as there are promising trends in the decrease in deforestation in the north-east of the Leuser Ecosystem in the district of Aceh Tamiang where landscape and jurisdictional programs have been established with support from the district government, Unilever, PepsiCo, and Musim Mas. Hopefully, these types of initiatives can be scaled up to deliver a rights-based approach to the protection and restoration of forests and peatlands across the Leuser Ecosystem. The Carbon Bomb Scandals show that the brands and traders sourcing from suppliers inside and around the Leuser Ecosystem must accelerate the scale and pace of these collaborative efforts because these globally important forests are still dying a death by a thousand cuts.

With the planet’s climate at an alarming tipping point and the biodiversity crisis threatening the existence of over a million species in the coming years, 2023 needs to be a year of increased ambition and commitments on the part of companies and governments to make good on the NDPE policies, Forest Positive pledges of Consumer Goods Forum members and climate and biodiversity pledges made by nations through the UN Forests and Climate Leaders Partnership, FACT Dialogue, and other initiatives launched during the last Conference Of Parties in Egypt.