Key Findings

- RAN and TheTreeMap have mapped the extent of canals illegally dug to drain peatlands in Indonesia’s protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

- High resolution satellite imagery captured by Pléiades Neo satellites enabled detailed analysis, which found a total of 253 kilometers of canals have been developed illegally inside the reserve, since the December 2015 palm oil sector cut-off date, including 139 km of canals developed after the December 2020 deforestation cut-off date of the European Union Deforestation regulation (EUDR).

- Ten primary canals make up 44 km, with the largest stretching 6.1 km—17% of illegally built canals in the reserve. These major canals are a high priority target for blocking and restoration.

- Canals have been developed to drain carbon-rich peatlands and enable land clearing and illegal palm oil development in the most intact areas of peat forests within the protected reserve.

- Collaborative action is urgently needed to stop deforestation and degradation of peatlands within the reserve—an area dubbed the Orangutan Capital of the World due to the high density of Sumatran orangutans that inhabit the peat forests.

The Problem

Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem is renowned around the world as the only place left where critically endangered orangutans, tigers, elephants, and rhinos still exist in the same forest. Located in the Sumatran province of Aceh, and spanning roughly 2.6 million hectares (6.4 million acres) of intact primary forest, the Leuser Ecosystem is widely considered one of the most important expanses of intact forest left in Southeast Asia. The most ecologically rich and vulnerable parts of the Leuser are its remaining lowland coastal forest and peatland regions.

The Singkil-Bengkung Trumon region is the largest, the most intact, and the most valuable of all these areas. Covering roughly 286,000 hectares (706,588 acres) in the southwest corner of the Leuser, Singkil-Bengkung Trumon is a worldwide hotspot for biological diversity and one of the highest-priority conservation landscapes on the planet. It comprises the critically important Singkil and Kluet peatlands—ancient, deep, and carbon-rich peatlands storing immense amounts of greenhouse gases safely and naturally underground. Its peatlands and surrounding lowland rainforests provide some of the last, best habitats critical to the continued survival of endangered Sumatran elephants, orangutans, and tigers.

The area has been called the “Orangutan Capital of the World” because it is home to the densest populations of orangutans anywhere. Avoiding the extinction of these iconic wildlife species requires keeping these lush forests standing. Despite its conservation value and importance to local communities, these lowland rainforests and peatlands face a renewed onslaught of new roads, canals, and deforestation for Conflict Palm Oil plantation development. Over the past decade, over 18,000 hectares (44,000 acres) of forests within the Singkil-Bengkung region have been cleared, leaving 234,000 hectares (578,000 acres) of rainforests remaining. This area decreases every year due to deforestation and the drainage of peatlands.

While there have been some encouraging developments in nearby regions, with deforestation rates dropping in some areas across Indonesia, the irreplaceable lowland forests of the legally protected Rawa Singkil have been subjected to an alarming spike in forest destruction. The process of this illegal deforestation begins with the arrival of heavy, earth moving machinery brought in to dig a network of canals for the purpose of draining the naturally saturated peat forests in preparation for industrial oil palm plantation development. RAN’s recent report, Orangutan Capital Under Siege, exposed this unfolding scandal by publishing unprecedented, high-resolution satellite imagery of the active incursion into the reserve.

At this high stakes moment, before more precious primary rainforest falls, it is urgent that all actors take decisive action to see that the newly dug canal system is blocked and the associated peatlands are restored to their natural ecological function.

The Evidence

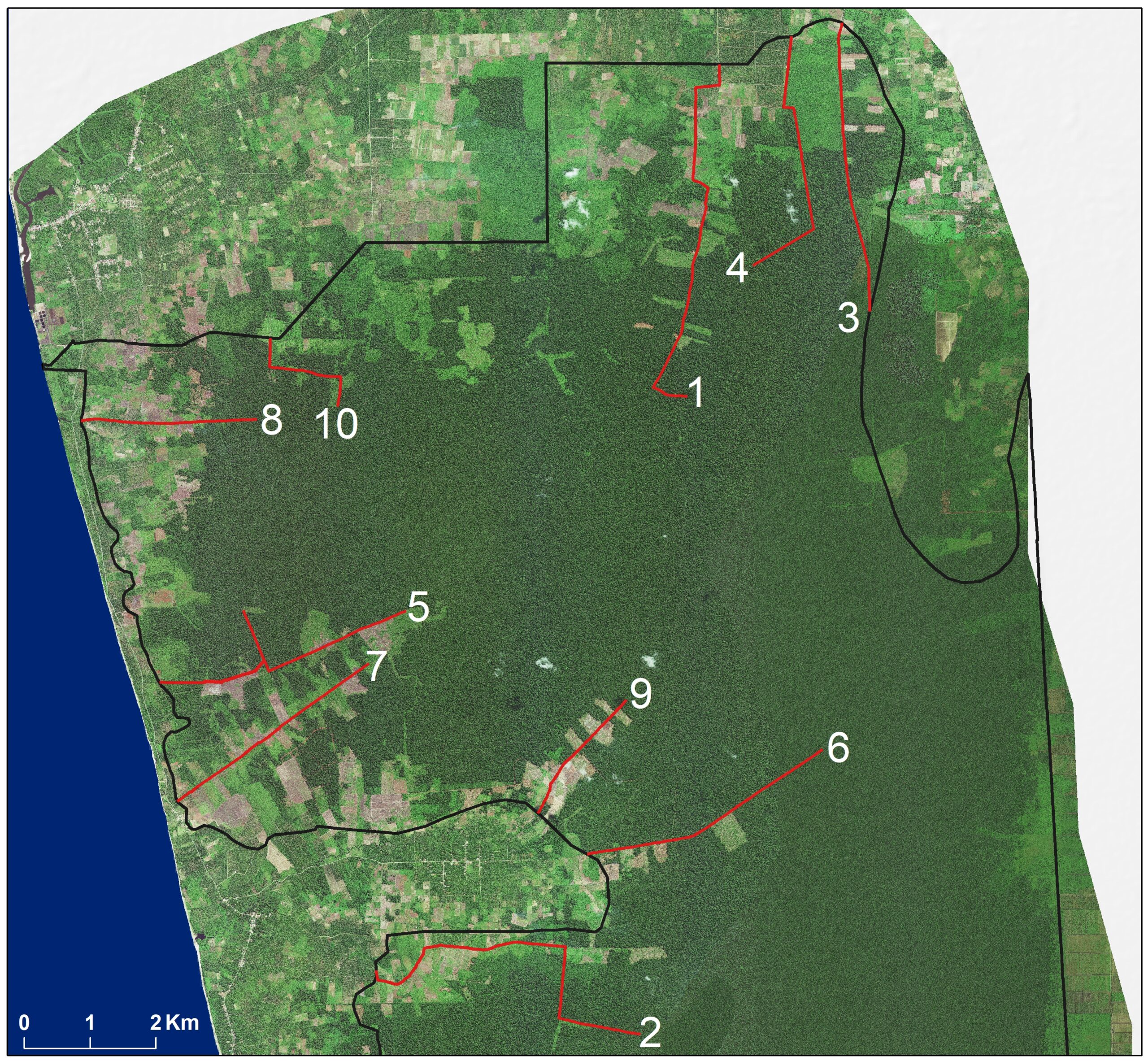

In July 2024, RAN commissioned satellites of Pléiades Neo to fly above the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve and capture high resolution images documenting the extent of illegal deforestation within the ‘orangutan capital of the world.’ These images provide unprecedented detail, allowing us to map the mosaic of illegal deforestation and oil palm production in the reserve and estimate the age of individual oil palms to determine when the clearance and planting occurred.

Alarmingly, deforestation was found to have increased inside the reserve after the adoption of ‘no-deforestation’ cut-off dates. The analysis, carried out by TreeMap, revealed 2,577 hectares (6,368 acres) of deforestation inside the nationally protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve since the December 2015 deforestation cut-off date adopted by the palm oil sector and major brands. Even more concerningly, it showed that the highest levels of deforestation, 74% of the total since 2016, occurred after the EUDR cut-off date of December 31, 2020. RAN’s ‘Orangutan Capital’ Under Siege report presented compelling evidence from field investigations that suggests that illegal palm oil could already be entering the supply chains of major global brands and traders.

Despite the exposure of the crisis unfolding in the Orangutan Capital of the World, deforestation within the protected peatland continued into 2025, including for new canals used to drain peatlands to prepare lands for more illegal palm oil plantations. In response, RAN commissioned The TreeMap to once again analyze the high resolution satellite imagery captured by Pléiades Neo, but this time to map the extent of illegal canals within the protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. The results are daming. We found a total of 253 kilometers of canals have been developed illegally inside the reserve, mostly in the northern third, since the December 2015 palm oil sector cut-off date, including 139 km of canals developed after the December 2020 deforestation cut-off date of the European Union Deforestation regulation (EUDR).

After analysing all the canals, RAN and TheTreeMap set about identifying the most destructive primary canals which should be the priority targets for blocking and restoration activities. Primary canals refer to the main drainage channels that serve as the backbone of the canal network. They are typically straight, and long, often extending over several kilometres, and are clearly visible in high-resolution satellite imagery. These canals extend deep into the reserve’s core zone, penetrating intact peat-swamp forest areas, where they enable land drainage and clearing, and connect downstream to rivers, facilitating the rapid outflow of water from the peatswamps. We found that ten primary canals make up 44 km, with the largest stretching 6.1 km—17% of illegally built canals in the reserve. These canals are a priority target for blocking and restoration.

The 10 main canals identified as primary in this report range from 1.9 to 6.1 kilometers in length and are directly responsible for altering hydrology at a landscape scale. In contrast, secondary canals are shorter and branch off from the primary canals. Given the scale of the crisis inside the reserve all the illegal canals need to be restored through collaborative action between the responsible government agencies and the actors driving this destruction––local elites that are behind the destruction, palm oil companies that control the mills and refineries sourcing from the reserve and global brands that have been repeatedly show for sourcing illegal palm oil from the reserve.

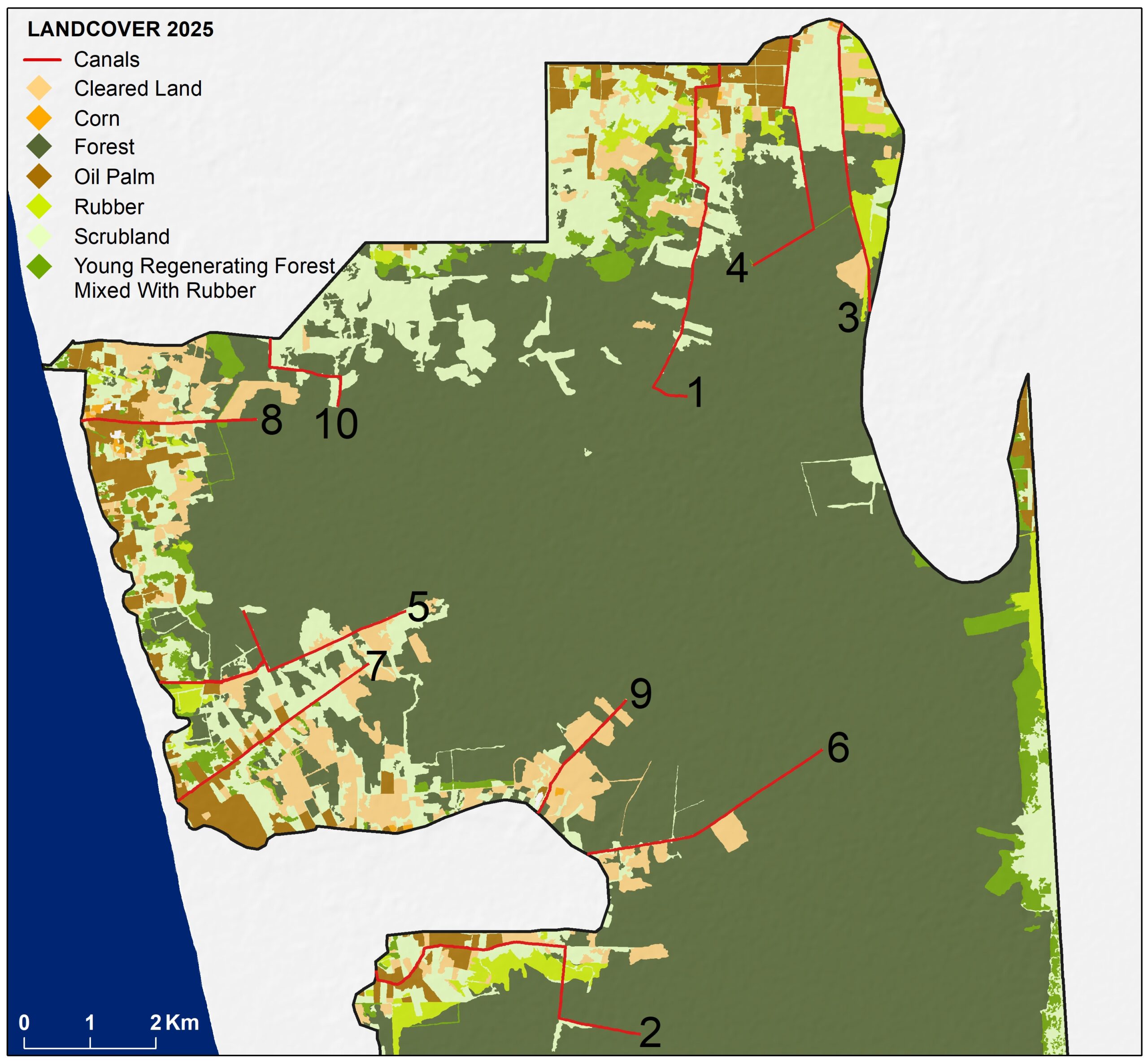

The ten most destructive canals are shown in the map below. These ten canals alone account for 44 kilometres of the total 253 kilometres of new illegal canals in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. Over 30 kilometers of these canals have been drained since the December 2020 cut-off date in the EUDR. These primary canals are a priority target for blocking and restoration activities.

Canals were mapped through visual interpretation of ultra high-resolution satellite imagery, including TripleSat (80 cm) imagery from 5 June 2016 and Pléiades Neo (30 cm) acquired between June and September 2024 to assess canal developments since the NDPE cut-off date of December 2015. The analysis was supplemented with Planet/NICFI imagery from December 2020 and March 2025 to assess canal development before and after the EUDR cut-off date, and to update the mapping to early 2025. To distinguish canals from roads and other linear features, we examined imagery for traits characteristic of water channels—such as straight lines, visible water presence, and connection to surrounding rivers.

This analysis builds on evidence published in November 2024 that documented the extent of deforestation and illegal oil palm plantations within the reserve. The map below shows the location of the new illegal canals overlaid with land cover identified within the protected area in 2025. The map shows that the development of canals is enabling land clearing into the most intact core area of the protected peat swamp. These areas of intact peat forests that are being opened up via illegal canal development and land clearing are areas of prime habitat for the Sumatran orangutan and play a vital role as carbon stores.

RAN and The TreeMap have now published the analysis on the extent of illegal canals in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve on Nusantara Atlas—a publicly available monitoring platform, powered by The TreeMap. This is the first time that high-resolution imagery of these illegal canals has been published, showing the extent of the palm oil-driven crisis in this protected wildlife reserve.

The table below shows the location of the ten priority canals for blocking and restoration within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. The GPS coordinates for the beginning and end of each canal (i.e location downstream and upstream) has been provided.

| Priority canal number | Length of canal (km) | GPS Coordinate Upstream | GPS Coordinate Upstream | GPS Coordinate Downstream | GPS Coordinate Downstream |

| 1 | 6.1 | 97.70784008160 | 2.80280195450 | 97.71215084090 | 2.84810211268 |

| 2 | 5.7 | 97.70142609430 | 2.71580923729 | 97.66537128000 | 2.72451592496 |

| 3 | 4.4 | 97.73265708700 | 2.81433602744 | 97.72886710520 | 2.85371866351 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 97.71673739720 | 2.82063264029 | 97.72198417580 | 2.85187658441 |

| 5 | 4.1 | 97.63581302030 | 2.76378194493 | 97.66946199790 | 2.77348404070 |

| 6 | 3.9 | 97.72623920170 | 2.75468721174 | 97.69414763140 | 2.74036724797 |

| 7 | 3.5 | 97.63828019340 | 2.74755509975 | 97.66439728960 | 2.76640987694 |

| 8 | 2.7 | 97.77526989480 | 2.61614226964 | 97.77496688990 | 2.64097684049 |

| 9 | 2.7 | 97.64914856840 | 2.79965409263 | 97.62516088810 | 2.79946879445 |

| 10 | 2.2 | 97.69948201850 | 2.76146101413 | 97.68741757510 | 2.74595940161 |

The Market Connections

Major brands implicated in the destruction of the Orangutan Capital of the World include Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Mondelēz, PepsiCo, and Nissin Foods. These brands risk exposure to illegal palm oil produced and sourced from the reserve through their sourcing from traders like Royal Golden Eagle Group, Golden Agri Resources and Wilmar, Musim Mas and Permata Hijau. All of these palm oil traders have been caught sourcing illegal palm oil from the reserve over the past five years, some most recently in November 2024. Japanese megabank, Mitsubishi UFJ has also provided USD $680.5 million in loans and underwriting to the Indonesian palm oil operations of Sinar Mas Group, Royal Golden Eagle and Wilmar between 2020 and June 2024.

A number of brands and traders have invested in programs that aim to end deforestation for palm oil production in Aceh–the Indonesian province where the Leuser Ecosystem is located. Early successes from these efforts have been documented by RAN in our recent report Ten Years in the Leuser Ecosystem: A Rainforest Frontier Driving a New Era of Landscape Conservation. However these programs have not yet focused on driving change in the district of Aceh Selatan where the highest level of illegal canal development, deforestation and illegal planting of palm oil plantations is taking place inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. RAN is calling on major brands and traders to take the next step by scaling up their commitments and investing in proven jurisdictional models in Aceh Selatan—and across the province of Aceh—to halt deforestation not just in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve but across the Leuser Ecosystem.