SHUSHUFINDI, Ecuador — Mention to Anita Ruíz the name of the giant oil company Chevron, and she trembles with rage. At her wooden hut here in the Amazon forest, where oil-project flares illuminate the night sky, she points to a portrait of her youngest son, who died seven years ago of leukemia at age 16.

“We believe the American oilmen created the pollution that killed my son,” said Ms. Ruíz, 58, who lives in a clearing where Texaco, the American oil company that Chevron acquired in 2001, once poured oil waste into pits used decades ago for drilling wells.

Texaco’s roughnecks are long gone, but black gunk from the pits seeps to the topsoil here and in dozens of other spots in Ecuador’s northeastern jungle. These days the only Chevron employees who visit the former oil fields, in a region where resentment against the company runs high, do so escorted by bodyguards toting guns.

They represent one side in a bitter fight that is developing into the world’s largest environmental lawsuit, with $27 billion in potential damages.

Chevron is preparing for a ruling by a lone judge in a tiny courtroom on the top floor of a shopping center in Lago Agrio, a town rife with slums that Texaco founded in the 1960s as its base camp in the Amazon.

Chevron faces claims for an era when oil companies were less purposeful about protecting the environment than they are today. It also faces potentially huge damages in a country where American corporations once wielded strong influence but are now treated with discourtesy, if not contempt.

The sympathies of the judge, a former military officer named Juan Nuñez, are not hard to discern, and he appears likely to rule against Chevron this year. “This is a fight between a Goliath and people who cannot even pay their bills,” Mr. Nuñez, 57, said in an interview in his office, where more than 100,000 pages of evidence were stacked to the ceiling.

But his ruling is not likely to end the case. Already, the dispute is the subject of intense lobbying in Washington, which could apply pressure to Ecuador on Chevron’s behalf. If the company loses, it is ready to pursue appeals in Ecuador and, if necessary, to seek international arbitration.

Texaco laid down stakes here in the 1960s, and began producing oil in the early 1970s when Ecuador was still under military rule. Before the oil began to flow, the region was inhabited by forest tribes, including the Cofán and the Siona-Secoya.

Political tension permeated Texaco’s presence in Ecuador much of the time it operated here in a partnership with the government, and by the time it was prepared to leave, in the early 1990s, a cleanup of its operations was needed.

So Texaco reached a $40 million agreement with Ecuador to clean a portion of the well sites and waste pits in its concession area, absolving it of future liability. But that cleanup, carried out in the 1990s, was far from the bookend Texaco hoped to achieve.

Instead, villagers in Ecuador became convinced they were getting sick from the pollution left behind. They filed suit in 1993 in the United States, and later claimed that their grievances were not covered by Texaco’s settlement agreement.

As the case snaked its way through American courts, Ecuador seemed to fall to pieces, going through 10 presidents in a decade by 2006. The American lawsuit was eventually thrown out, on grounds the case should not be tried in the United States, and the plaintiffs reformulated it and filed it here.

Today, Chevron has absorbed Texaco, and Ecuador has gone through a metamorphosis under the leftist President Rafael Correa. He has repeatedly sided with the plaintiffs, calling Chevron’s Ecuadorean past “a crime against humanity.”

Such sentiment holds strong appeal to those who claim that people here, like Ms. Ruíz’s 16-year-old son, are dying from the pollution that Texaco spawned. Citing scientific studies, the plaintiffs claim that toxic chemicals from Texaco’s waste pits, including benzene, which is known to induce leukemia, have leached for decades into soil, groundwater and streams. A report last year by Richard Cabrera, a geologist and court-appointed expert, estimated that 1,400 people in this jungle region — perhaps more — had died of cancer because of oil contamination.

Chevron rejected the claims, contending that Mr. Cabrera had no medical evidence to back up his conclusion that the company should pay $2.9 billion just to compensate for excess cancer deaths.

The lawsuit here focuses more on environmental cleanup than cancer deaths, but the issue remains hotly disputed, particularly after a judge in California dismissed a separate claim against Chevron for cancer deaths in 2007, finding that false claims had been put forth by the plaintiffs’ lawyer, Cristobal Bonifaz, who was instrumental in starting the fight against Texaco in the 1990s but is no longer involved in the suit.

Nearly every other detail in the case is disputed as well, save one: Chevron and the plaintiffs agree that the expansion of oil exploration in northeastern Ecuador spoiled what had once been a pristine jungle.

More than four decades later, evidence of the contamination is unavoidable at well sites near Lago Agrio and other towns in the region.

Some pools of waste dug by Texaco combining noxious drilling mud and crude oil still lie exposed under the sun, seeping into nearby water systems.

Other pits, ostensibly cleaned up by Texaco after the company handed over operations to the national oil company, Petroecuador, have varying amounts of pollutants near the surface, leading to clashes among scientists for the two sides about the exact levels and their health implications. Petroecuador has a poor environmental record of its own and faces criticism for at least 800 oil spills since 1990.

In what may be the most contentious part of the legal battle, Chevron argues that it cannot be held responsible for damage done by Petroecuador after it took over the site, or by the Ecuadorean government’s broader project to colonize its jungle frontier, which brought more than 40,000 settlers to the region by the 1970s using roads that Texaco built.

The plaintiffs claim Chevron must be held responsible for the damage where Texaco once operated, up to the present, claiming the systems put in place by Texaco allowed Petroecuador to go on polluting. If Chevron has a problem with that, said Steven Donziger, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, then it should sue Petroecuador.

“The damage caused by Texaco is still causing harm more than 18 years after Texaco ceased operating, and will continue to do so for centuries until it is cleaned up,” Mr. Donziger said.

Despite the potential size of the damages, Chevron insists its solvency is not at stake. But the legal battle is denting the company’s environmental image. Ecuador’s attorney general last year indicted two of Chevron’s lawyers, accusing them of fraudulently conspiring to prove that Texaco had cleaned up waste pits.

That maneuver infuriated Chevron. “In politicizing and corrupting the case as much as they have done, they are signing on to 10 or 20 years more of litigation,” said Silvia Garrigo, a lawyer who is Chevron’s manager of global issues and policy. “Any enforcement action is going to be met with a challenge by us.”

Chevron has fought back with trade lawyers and lobbyists, using highly paid talent like the former United States trade representative Mickey Kantor, and the former Clinton White House chief of staff Mack McLarty to push the Obama administration to strip Ecuador of trade preferences, on the grounds that it broke its agreement to absolve the oil company of liability.

“I can’t warrant what Texaco did 42 years ago or 40 years ago or 35 years ago,” Mr. Kantor said. “All I know is they spent $40 million to clean it up. They were given a release signed by the government of Ecuador and Petroecuador.”

The lobbying effort in Washington appears to be an effort to pressure Ecuador to come to the table and work out a deal. “We want to resolve this in a reasonable fashion,” Mr. Kantor said.

Texaco may be gone, but the destiny of people near Lago Agrio is still intertwined with that of the United States, and anger simmers here. Those who claim to have suffered the greatest harm face years of delay, at best, before any payout. Some may not live to see the case resolved.

José Guamán, 62, acknowledges that possibility. He lives near a well once operated by Texaco. Guiding a visitor around his property, he pointed to a covered waste pit where his late wife, María, once fell and emerged covered in black ooze. She died at 45, leaving behind their two children. Mr. Guamán said he did not know what had caused her death.

“But if I know one thing, it is that petroleum curses anyone who touches it,” Mr. Guamán said. “If that applies to us, then it should apply to the Americans as well.”

Residents of Shushufindi, Ecuador, wash in the water of the Santa Fe River. The residents say toxic chemicals have leached into the soil, groundwater and streams.

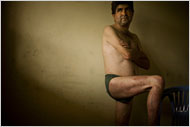

Wilmo Moreta of Shushufindi says contaminants caused his skin ailments.

Mercedes Jimenez lives next to an oil well and complains of headaches.

Simon Romero reported from Shushufindi, Ecuador, and Clifford Krauss from Houston.