In the U.S. we often speak of environmental justice as an idea: a concept that guides our work, a state of ecological equity that we strive toward.

But for the people here in Ecuador living with the massive oil pollution deliberately dumped here by by American oil company Texaco from 1962 to 1992, the concept of environmental justice is never abstract. For them, it’s a matter of survival, a day-to-day struggle to stay alive and keep their children healthy.

After two decades of putting up a heroic fight, the Ecuadoreans who have been living with Texaco’s oil pollution for decades have yet to see a dime for cleanup of their land and water. Earlier this year, we worked with these Ecuadoreans—as well as Amazon Watch, Groundwork Opportunities, and Saving an Angel Foundation—to launch ClearWater, a project that aims to deliver clean, drinkable water to the people of the Ecuadorean Amazon.

The pilot project provided rainwater catchment systems to two communities, but now we need to roll ClearWater out to dozens more. I’m down here with a team from the San Jose State University chapter of Engineers Without Borders to examine the oil contamination in the area and the existing water catchment systems so that they can use their engineering expertise to help figure out how best to provide clean drinking water to all the communities that need it.

Our first stop was the house of Guillermo Grefa in the Quechua community of Rumipamba. Guillermo’s house was the site of a massive oil spill in the 80s when a Texaco pipeline ruptured. To this day, oil pipelines still run by and underneath his house—which is nothing out of the ordinary for this area, sadly, since you have to drive along miles and miles of oil pipelines to get here.

Paul Friedlander, one of the engineers here with us, says that even though he’d read about the oil pollution down here, he was not prepared for what we’ve seen so far. “It’s one thing to see pictures of the contamination, but to actually see it at the location, and hear the people talking about it, and the effect on their lives, really brings it home,” he says. “It’s heartbreaking to see.”

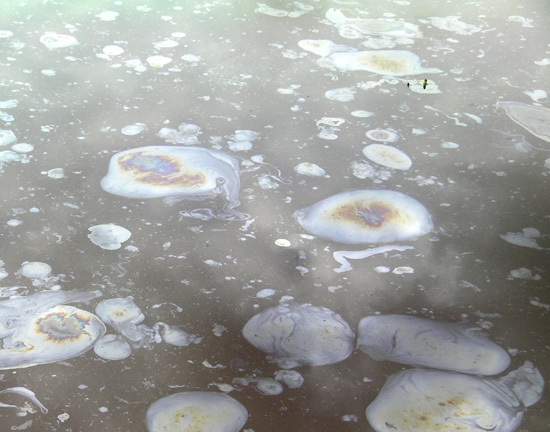

I’ve worked on this campaign for nearly two years and even I wasn’t prepared for what I saw at Guillermo’s house—oil still sits on top of the pond behind the house to this day, 30 years after the spill. Ecuador’s state-run oil company, PetroEcuador, which was a non-operating partner with Texaco at the time of the spill, is paying several locals to clean up the mess behind Guillermo’s house. In all this time, they’ve still only managed to clean up about 40 square meters.

Seeing this pollution firsthand, and the resolve of the people living with it, also brings home just how important the ClearWater project is.